chesapeake bay

Like it or not, we live in an age of short attention spans. How many times have you started into a video or blog post that sounded interesting, only to abandon it after the first few seconds because it was just too long and drawn out? I have to admit that, before I open any video on social media, I look to see how much of a time investment I’ll need to make. It’s especially true with instructional videos. When I turn to YouTube or Facebook to find out how something works, I want to see content that is quick and to the point.

That’s why I’m introducing my new short video series, The Chesapeake Minute. It’s a series of instructional vignettes about light tackle fishing that get right to the point. Most entries will be 60 seconds or less and I’ll never go over two minutes. Look for entries about angling techniques, lure selections, gear choices, hot locations, fishing reports, and other light tackle related advice designed to help you quickly maximize your success on the water.

Most of the videos will be season specific, but I’ll also throw out some tips that work any time of year. I pledge at least 36 episodes in 2020 and there will likely be many more. A new entry will drop every Thursday afternoon at 3:00 PM with bonus editions coming out at other times through the week.

I’ll announce some of the entries on social media, but you can follow my YouTube Channel to make sure you don’t miss an episode. The Chesapeake Minute Playlist is fully indexed and searchable so you can easily find any subject you’re interested in. They’ll be easy to find on YouTube Search and Google Search as well. Just type my name and the fishing subject in the search box.

A few videos are already live and look for more over the next couple of weeks since my goal at first is to cover most of the light tackle fishing basics. I’m also open for suggestions, so fire away. I’ll still post some full-length videos from time to time, but I hope you’ll push the PLAY button and give my new series a look. It only takes a minute!

If you do a keyword search for “invasive species” on any Chesapeake Bay-centered social media platform, you’ll most likely see more than you want to know about northern snakeheads. But, there are lesser-known invasives in the Chesapeake watershed, some that aren’t considered harmful and that are even stocked by our state natural resource agencies. I’ll leave it up to the experts to decide when it’s alright to promote a new species or when it’s better to eradicate one, but I can tell you for certain that I’m tickled pink about the rise of the redear sunfish.

Redear sunfish (Lepomis microlophus), also known as shellcrackers, are one of my all-time favorite fish. Some of my fondest fishing memories are of catching burlap sacks full of shellcrackers with my brothers and our father. Originally considered a strictly southern species, they’ve been helped along by selective stocking while naturally expanding their range north. In 1938, they were reported to be no farther north than Georgia but by 2011, they had made their way up to the Potomac River tributaries. In the past five years, I’ve caught them in many Eastern Shore tidal streams and in every DNR-managed lake that I’ve fished. Shellcrackers do great in this area because of their high tolerance for salinity and their taste for small snails and other mollusks. Today, the shellcracker populations in our tidal streams and millponds are booming.

Read More!

As the Chesapeake summer slowly slips into fall, many anglers are looking forward to the upcoming rockfish run. But don’t wave goodbye to summer fishing patterns just yet. Unless you’ve been hiding under a bridge, you’ve probably heard about the incredible bull red drum catches south of Poplar Island. We seem to get more redfish every year in Maryland, and this has been the best season in recent memory.

At one time redfish, or channel bass as they are sometimes called, were so prolific that anglers caught them by the boatloads. Fishing pressure increased every year until the early-1980s when stock assessments showed big problems. Regulators stepped in and eventually declared a complete moratorium on the harvest of redfish greater than 27 inches on the East Coast. It is taking the species a long time to recover. Red drum have an estimated 30 year lifespan and some can live up to 60 years. Removing any spawning-age fish from the overall population has implications. Bigger and older fish can drop as many as forty-million eggs per season. That’s ten times as many eggs as younger ones. Killing a single bull red can impact the health of the species.

Read More!  I quit rockfish. Yes I did. Well, at least for a while. I haven’t fished for striped bass since December 6, 2017. That was the day we landed three huge stripers including a 50-incher just below Poplar Island. It seemed like a good stopping point.

I quit rockfish. Yes I did. Well, at least for a while. I haven’t fished for striped bass since December 6, 2017. That was the day we landed three huge stripers including a 50-incher just below Poplar Island. It seemed like a good stopping point.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I haven’t quit fishing, nor have I given up rockfish for good. In fact, I’ll be back on them next week. I just decided to spend the winter/spring of 2017-2018 fishing for perch, crappie, and shad.

You know what? I’ve had a blast!

I can’t resist the call of the creeks. I dearly love striper fishing, but the hours I’ve put in polishing my rockfish techniques add up to only a fraction of the time I’ve spent in my life-long pursuit of panfish. They are my first love. After over fifty years of fishing, my favorite fish remain bluegill, crappie, perch, and shad.

The longer I live and the more I fish, the more I long for simplicity. To me, panfishing is therapy; a welcome counter to the competitive and frequently fast-paced world of run-and-gun striper fishing. I can stand on the creek bank for hours casting for perch or crappie. It makes me feel like I’m connected to nature, not only as an observer, but as a participant. When I’m panfishing, I never think I’m wasting a minute. In return, panfishing has enhanced my striper fishing skills. The pursuit of perch has made me a better rockfisherman.

UPDATE: This post appeared earlier on ChesapeakeLightTackle.com. It has been reprinted due to recent proposals to require circle hooks year-round for bait fishing in Maryland.

UPDATE: This post appeared earlier on ChesapeakeLightTackle.com. It has been reprinted due to recent proposals to require circle hooks year-round for bait fishing in Maryland.

It’s spring in the Chesapeake Bay and time for big migratory stripers. Some of the biggest striped bass in the world are caught in Maryland in the early spring. A few fishermen are already using circle hooks to catch & release big fish on the points near the rivers using bait such as bloodworms and cut menhaden. Circle hooks aren’t just a good idea for bait fishing in the Chesapeake Bay, they’re required by law. Maryland fishermen have been slow to see the advantages of circle hooks. I think that’s because most of us haven’t used them enough, but there’s also confusion about what circle hooks are and how they work. I recently had an opportunity to travel to Providence, Rhode Island to attend a FishSmart conference sponsored by NOAA about catch & release techniques. I came away with some interesting information.

According to extension agents working with Florida Sea Grant, circle hooks have been used for decades in their state by both recreational and commercial fishermen who appreciate their ability to efficiently catch fish. The principle behind the hook is simple. After the hook has been swallowed, the fisherman applies pressure to the line, pulling the hook out of the stomach. The unique hook shape causes the hook to slide towards the point of resistance and embed itself in the jaw or in the corner of the fish’s mouth. The actual curved shape of the hook is intended to keep the hook from catching in the gut cavity or throat.

The advantage to the fisherman is that hooking is automatic. No hook set required. All we have to do is let the fish swim off with the bait then pick up the rod and start reeling. Circle hooks are a fool-proof way to catch stripers when fishing with bait, but do they work to protect the fish?

According to Maryland rockfish scientist Rudy Lukacovic, most of the time they do. Most fishermen will tell you that they still see gut-hooked fish occasionally. That’s one of the drawbacks to bait fishing, but there’s also another problem. There is unfortunately no industry standard as to what makes a circle hook. In fact, some of the hooks you buy off the bait shop shelf may not be circle hooks at all. Just because it says circle hook on the package doesn’t mean it is. There are impostors.

According to Maryland rockfish scientist Rudy Lukacovic, most of the time they do. Most fishermen will tell you that they still see gut-hooked fish occasionally. That’s one of the drawbacks to bait fishing, but there’s also another problem. There is unfortunately no industry standard as to what makes a circle hook. In fact, some of the hooks you buy off the bait shop shelf may not be circle hooks at all. Just because it says circle hook on the package doesn’t mean it is. There are impostors.

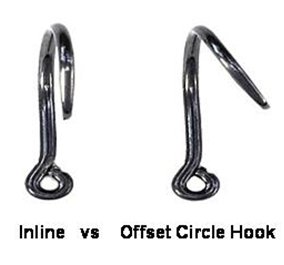

On a true circle hook, the tip of the hook points back toward the shank of the hook. If it points toward the eye, it’s not a circle hook no matter what it says on the package. Confused? Then try this: Curve your index finger around the contour of the hook shank and press down a little. If you feel the tip of the hook pricking your finger, it’s not a true circle and won’t work right. The tip of the hook should curve away from your finger.

it says on the package. Confused? Then try this: Curve your index finger around the contour of the hook shank and press down a little. If you feel the tip of the hook pricking your finger, it’s not a true circle and won’t work right. The tip of the hook should curve away from your finger.

Circle hooks can be roughly divided into two types, offset and non-offset. The offset refers to the amount of deviation in the plane of the hook point relative to that of the shank. Most of the hooks you see on the store shelves are offset. That means when you lay them down on a table, they won’t lay completely flat. A true non-offset hook will lay perfectly flat on the table. Offset circle hooks are more likely to gut-hook your fish.

Since there can be confusion about what constitutes a true circle hook, some tournaments are specifying certain brands and types as tournament legal. Unless the industry responds by standardizing descriptions, state resource departments and lawmakers may also have to be more specific. Maryland defines a circle hook as: A non-offset hook with the point turned perpendicularly back to the shank. Circle hooks used in bait fisheries should be “non offset”. That is, if the hook is laid on a flat surface, all parts of the hook lie flat on the surface.

Since there can be confusion about what constitutes a true circle hook, some tournaments are specifying certain brands and types as tournament legal. Unless the industry responds by standardizing descriptions, state resource departments and lawmakers may also have to be more specific. Maryland defines a circle hook as: A non-offset hook with the point turned perpendicularly back to the shank. Circle hooks used in bait fisheries should be “non offset”. That is, if the hook is laid on a flat surface, all parts of the hook lie flat on the surface.

Here are some tips for using circle hooks to catch striped bass:

Keep it limber – Use a slow, limber fishing rod with a lot of bend in the tip. A stiff, fast-tipped rod is more likely to pull the hook out of the striper’s mouth when you pick it up. Ugly Stix fans, this is your cue!

Don’t bury the hook in the bait – If you hide the hook, it is less likely to catch the corner of the fish’s mouth when you start reeling. If you use live bait, hook the bait through the nose or lips so the hook is completely exposed and the gap isn’t blocked. Stripers won’t see the hook and your bait will look more natural.

Crank, don’t yank – Just set your reel to free spool, wait for the fish to take off and start reeling. If you’re live-lining, count to ten before you start. Don’t set the hook.

No need to sharpen – Sharpening a circle hook will damage the tip and make less likely to hook the mouth but more likely to hook the fish’s stomach.

Stay away from stainless – If a fish breaks off, the stainless hooks don’t rust. That means it will stay in the fish’s mouth longer. If a fish swallows a stainless hook, it will probably die.

Go big or go home – Don’t be afraid to use a big hook. A 8/0 or 9/0 hook is great for stripers. Take a look at the big rockfish in the picture below. It takes a wide-gap hook to get over those thick lips! Hooks with a gap that are too small are more likely to gut-hook the fish. For big fish in the  spring, use 10/0 or even bigger. Also, pay attention to the quality of the hook because you don’t want a hook that will bend or straighten.

spring, use 10/0 or even bigger. Also, pay attention to the quality of the hook because you don’t want a hook that will bend or straighten.

Catch & Release Tips

Be Prepared – If you aren’t used to using circle hooks, it might take a little longer to remove the hook from your fish. Keep your pliers, de-hooker, measuring device, and camera beside you and ready to use. If the fish swallows the hook, just cut the line as close as you can to the hook. Don’t try to pull the hook out if it’s embedded in the fish’s stomach.

Do you really need a net? – It’s a lot easier just to reach down and lip the fish with wet hands or wet rubber coated gloves. Nets cause you to lose fish and they injure them by removing slime. If you must use one, find one that has a fine, rubber coated mesh. You might even consider a a cradle net since that will let you measure your fish in the water.

Handle With Care – If you plan to release a big fish, be sure to support the body weight with both hands. If you have to lay it down to remove the hook, do it gently. Try not to drag the fish through the mud or sand because this can injure it and remove slime. Get the fish back in the water as fast as you can.

In a nutshell, circle hooks are good for the fish because fewer stripers are hooked in the stomach or in other vital organs, and they’re good for the fisherman because they increase hook-ups and reduce missed strikes. Good for the fish, good for the fisherman – that’s a winning combination.

Did you know? Circle hooks have been around for centuries. Archaeologists have recovered stone circle hooks that are tens of thousands of years old from the grave sites of indigenous cultures. J hooks came about relatively recently because they are easier to make. Once again, modern-day anglers are recognizing the benefits of circle hooks for both efficiency and conservation. This fishing technique, like the hooks themselves, has come full circle.

By now, you’ve probably noticed that many Chesapeake Bay light tackle anglers are using skirted jig heads when they fish with soft plastic lures. Jigs with silicone skirts are becoming extremely popular in the Mid-Atlantic region and there’s no doubt that they make deadly baits for big striped bass. A skirt on a lead jig head with a soft-plastic bait increases action and creates a wider profile in the water. Skirts also provide color and contrast, two essential big-fish strike triggers.

By now, you’ve probably noticed that many Chesapeake Bay light tackle anglers are using skirted jig heads when they fish with soft plastic lures. Jigs with silicone skirts are becoming extremely popular in the Mid-Atlantic region and there’s no doubt that they make deadly baits for big striped bass. A skirt on a lead jig head with a soft-plastic bait increases action and creates a wider profile in the water. Skirts also provide color and contrast, two essential big-fish strike triggers.

Skirts on lures aren’t anything new. They got their start in the mid 1920s in Akron, Ohio where Fred Arbogast worked for the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. He and his fishing buddies experimented with slicing thin rubber sheets into narrow strips and attaching them to their spinning lures. They caught fish. After Arbogast won several fishing competitions, he took out an ad in the June, 1926 edition of The Hunting & Fishing Magazine. His lures caught on quickly so Fred quit his job at Goodyear to form the Arbogast Lure Company. Read More!